Our last blog post was about expanding the hobby beyond blank fire battles and the inherent problems with only focusing on “trigger time.” Now, we will go much deeper.

Years ago some friends and I came up with a way to make immersion events more

realistic. We devised an idea to create a defined area, a "zone", in which

nothing after 1945 was permitted, including conversation. Discussion

topics were limited to things soldiers might have discussed in WWII. If

you were “in the zone,” ONLY period-based things were allowed. People

who wanted to talk about the hobby, or TV shows, or who wanted to pull

out something anachronistic, had to step away. At first, it was

challenging. But with time, we were able to hone this skill. It became

possible to exist in a simulated wartime atmosphere for hours at a time,

within our "zone."

One thing we quickly learned was that some settings

or events were more conducive to our zone than others. It was the same with people. Some were more adept at getting into the necessary mindset,

sticking with it, and helping others get there, too. We called these

places and people "zoney."

Over time, we have come to a

different understanding of “zone.” We no longer narrowly define it as

just a physical area where modern talk and items are barred. We have come to

realize that zone happens in the mind. It requires not only a solid

foundation in period historical knowledge, but also imagination,

including the ability to look at something absurd, or anachronistic, and

be able to work it in to a period mindset. Zone, for us, is both the

non-tangible, theoretical metaphysics of reenacting, and the hard,

existential aspect of things that exist in the world. It is both mental

and physical. If he chooses to do so, one person, alone, in nearly any

setting, can put himself in the zone. Zoniness is a word we use that describes those intangible aspects of a

person, place or thing that make it suitable for creating a feeling of,

"this is what it may have been like." Often zoniness is a

subjective evaluation, a quality impossible to measure or quantify. It

is entirely separate from the concept of authenticity. A brand-new

reproduction bread bag, for example, can be a totally authentic thing

from a material culture standpoint. However, a well-used post-war bread

bag, showing age and use, with repairs and obvious traces of wear, may

be a more zoney thing, even if it is objectively less authentic than a

reproduction, due to some minor and easily overlooked construction

feature. Zoney items evoke an emotion, a feel. A zoney item, if it could

talk, would tell a story about the war. Further, such items allow us to

become part of that story.

In Sicherungs Regiment 195 we

believe that reenacting is mostly a mental and cerebral experience. The

uniforms, field gear, food, camp setting, etc. are all simply “props”

to aid entering a conceptual realm conducive to a period-based mindset

and/or historical-based experience. Zoniness is what we strive for at

events. A grassy meadow, a stream at the base of a hill, a dilapidated

old barn, an abandoned stretch of railroad track- these are zoney

places. Pocket trash, wartime-type rations and carefully-chosen personal

items are zoney things. Someone could be wearing all original gear, but

if he cannot get in the mindset, and speak and act like the historical

character he is portraying- he is zoneless. That is not a zoney dude.

His uniform and field gear might be really zoney, but not him. In

contrast, 3 people in modern clothes, sitting in a Taco Bell, could have

a really zoney period discussion. Rain on the evening before a D-Day

event is zoney. Modern conversation topics, period objects used in a

non-period manner, and general farb, are not.

Zoniness is the

exact reason why all modern items are banned from our unit. It is the

reason chairs and camp furniture are banned. It is the reason why every member of the unit

is required to have a fully fleshed-out first-person persona. It is the

reason we don’t like “trigger time.” It is the reason we are very

different type of unit than most living history organizations.

There

is more to reenacting than putting on a uniform and shooting blanks at

people. This is reenacting 101. It’s how you get introduced to the

hobby. It’s the lowest common denominator. Many never grow out of this

stage. Others go far beyond it…

See you in the Zone.

A WWII living history group seeking to recreate the average, day-to-day, mundane experiences of the common German second-line security soldier. Visit our web site at www.festung.net. E-mail: intrenches1945@gmail.com

Tuesday, February 24, 2015

Monday, February 9, 2015

Beyond the Blank Fire: A realistic approach to recreating life in WWII

WWII reenacting has traditionally centered on

public displays, which are ostensibly for educational purposes, and private

combat simulations that are usually referred to as "tacticals." In

tacticals, reenactors take to a make-believe battlefield, and blast away at

each other with real or simulated weapons until the end of the event.

Participants usually state that they take part in tacticals to get a feeling

of, "this is what it may have been like." Unfortunately, as most any

long-time reenactor will readily admit, there is simply no way to realistically

recreate field combat in WWII. There are few, if any, tanks or aircraft, few

heavy weapons, no artillery. Reenactment combat generally happens at, or

near, hand-to-hand distances- not the ranges at which Wehrmacht strategists

anticipated- which makes reenactment use of correct tactics difficult or

impossible. Further, the realities of reenactment sites often necessitate

attacking positions from directions that would not be feasible, or defending

positions unsuitable for defense. Virtually no reenactment unit actually takes

the field in Bataillon or even Kompanie strength -- independent units of 10-15

guys are typical at a reenactment battle. In the reality of war, it is possible

to aim, and fire, at a target nearby and miss. Additionally, many soldiers likely

were hit by unaimed shots fired from great distances. Blank-fire simulated

combat is, on the whole, a very poor way to create a realistic representation

of something that really happened. Worse, "public tacticals," for educational

purposes, are entirely unsuitable.

In Sicherungs-Regiment 195 we strive to precisely recreate a

historical place and time. This mandates an approach starkly different from reenacting as it has traditionally been understood. Firing a blank at a reenactor and feeling indignant

when he does not "take a hit" is boring and puerile, and typically

leads to disappointment, animosity, and hobby burnout. We seek a more realistic

and immersive experience. Those of us who founded this unit are all "veterans"

of the blank-fire "combat" scene. Whatever thrill or rush might once

have been obtained from the bangs and flashes of a sham battle are long-gone.

What remains, though, is a passion for historical recreation. Bringing the past

to life through painstaking recreation of all details of an earlier era is

truly central to reenacting; it is the crux of our hobby. That is what is

important. The means of this recreation, or the choice of activity being

recreated, are secondary things.

Spending a night in a foxhole, without firing a shot, is a very realistic experience. (505th RCT D CO)

Are there activities that can be recreated in a more authentic way,

that can better give a true feeling of "this is what it may have been

like?" Absolutely. There is no doubt that the lure of the tactical draws

many people to our hobby. But, truth be told, paintball or airsoft, where real

projectiles are flying through the air, may be a more realistic option for

those who want the feel of hunting and being hunted -- to say nothing of the

real military, which undoubtedly attracts many young people yearning for a

taste of battle. It is our belief that focusing the WWII reenactment hobby on

hoak battles does our hobby a disservice. Demographics are changing, most

reenactors are no longer the sons of the WWII veterans. A more diverse hobby

with a wider range of options for participants could be larger, and more

inclusive, without any compromise on authenticity. It is no secret that many,

or most, reenactors would not be considered fit for real front-line combat duty.

Yet, paradoxically, virtually all

reenactment groups exclusively portray line infantry units. It is our hope that

this will change, and we see ourselves as part of this change.

Even units portraying combat infantry formations need not be

centered exclusively on blank-fire combat. Soldiers in every kind of unit deployed

to an area of operations. There, they set up quarters, prepared and issued

rations, performed drill, marched, had inspections... As the old saying goes,

"War is hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror." A

focus on battle reenactments means endlessly attempting to repeat those moments

of terror, while avoiding all those hours of more typical, and often mundane

experiences. Field soldiers constructed positions, manned observation posts and

foxholes, performed scout/reconnaissance and security patrols, stood sentry

duty, and ran messages to rear areas. All of these are things that can be

realistically portrayed, with the men and means available to a reenactment

group.

Patrols do not always have to end in engagement. Sometimes nothing is found. (Unknown unit)

We are a rear-area unit and we have no shortage of events that we

can participate in while being true to our rear-area impression. Last week, a

WWII German reenactor in Texas was shot at a battle when a GI reenactor began

firing live rounds. That is a commitment to realism that we will not make. In

other scenarios, we readily find the authenticity we seek, without any

compromise.

Roadside sentries (Sicherungs-Regiment 195)

We reject the notion that tactical battle reenactments are necessary

for our hobby. Use of real weapons in an increasingly complex world of state

firearm regulations and noise ordinances actually make reenactments more

difficult. We embrace the idea of a hobby in which battle scenarios are just

one type of private event, no more important than other events, which do not

offer a "trigger time" option. We call for all reenactors to keep an

open mind, and consider non-combat immersion events with varied scenarios. Our

hobby can thrive even without blank-fire tactical if we choose to focus on the

historical recreation, which is at the very heart of what we do. Last month,

some of our members helped with a Wehrmacht headquarters clerk office vignette at the annual Battle of the Bulge event at Fort

Indiantown Gap PA, the largest WWII event on the East Coast. We issued

identification documents and passes to hundreds of event participants. The

positive feedback on this functional recreation of a Wehrmacht office was

overwhelming. While typewriters and fountain pens have a limited appeal, such a

vignette could be incorporated as one part of any field immersion event,

together with countless other realistic impressions that would not necessitate any opponent at all.

We understand that tacticals will always be a

part of the WWII reenactment hobby. However, we desire to serve as a constant

reminder that, just as line infantry is only one of a myriad of possible

portrayals, combat is just one of countless activities in wartime soldier’s

life. These other countless activities can serve as the focus of an immersive

and zoney event.

Soldiers construct a network of noise makers/listening posts. (3.Panzergrenadier-Division)

Friday, February 6, 2015

Insert pages for the Soldbuch

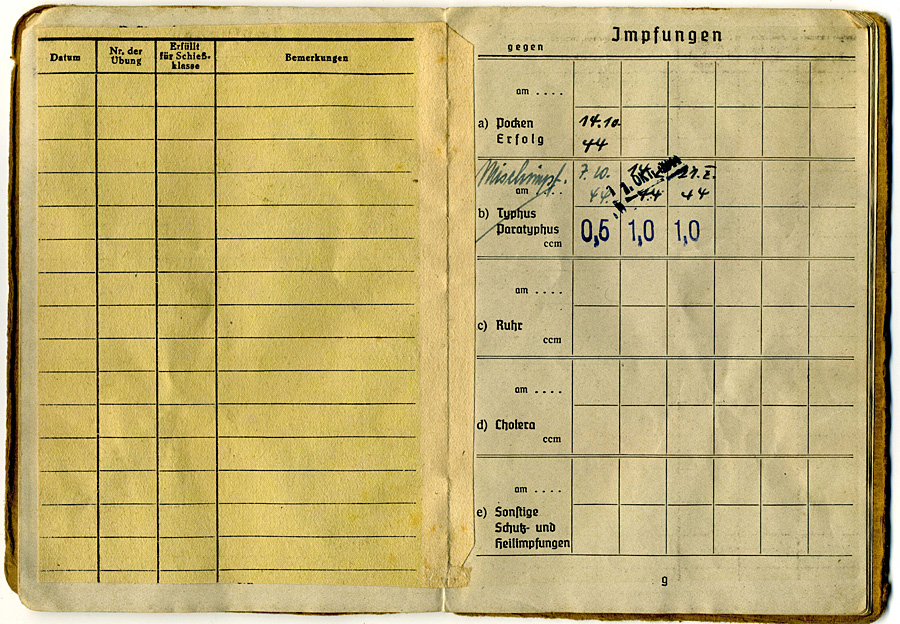

Every soldier in the Wehrmacht was issued a paybook and identification document called the Soldbuch. Original Soldbücher commonly had additional pages pasted in to record things for which the book had no space. Here are a few which we have reproduced and used.

The insert is printed on both sides and folded in the middle to make four pages. It is loose in the book, it may have been glued in at one time. Only one of the four pages has entries. Both sides are exactly the same.

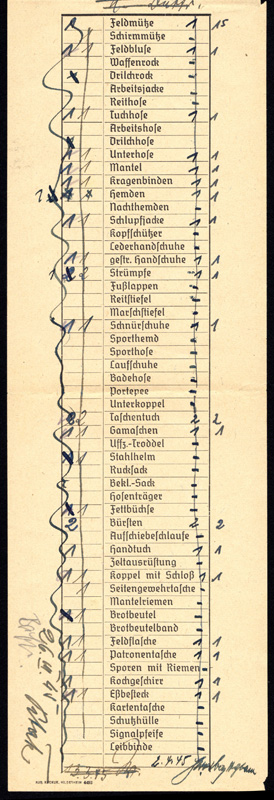

EQUIPMENT ISSUE

The first pattern of Soldbuch as made and

issued in 1939 had a very limited amount of space on pages 6 and 7 to

record the items a soldier was issued. The pre-printed item list omitted

many basic items issued to nearly every soldier, such as ammunition

pouches, clothing bags, or the Zeltbahn, and there was very little space

provided to add these in, and no space for the many other items often

recorded on these pages, such as Gamaschen or special clothing items. To

fix this problem, later patterns of the Soldbuch

had many more items pre-printed on these pages, along with more space

to record items not present in the list. However, very many books were

made and issued with the first batches in 1939, and stocks of these

early books continued to be issued throughout the war. To update these

books, and also to add more space in cases where these pages were filled

with entries after years of service, a wide variety of inserts were made to be pasted into the Soldbuch. Some were fairly close copies of the equipment issue pages in later pattern books, others were more elaborate fold-out inserts.

The equipment issues and checks were fairly frequent for many soldiers,

these were conducted when a soldier was transferred, deployed to the

field, or at various times when equipment reissues took place. In any Soldbuch that was carried for a few years by a soldier who saw field service, it is typical to find at least one of these inserts.

This page would be pasted at the top onto the top of page 7 in the Soldbuch,

then folded in the middle with the lower half folded up and over the

upper half, to enable it to fit neatly in the book (you can see the

crease from the fold on the line that says "Portepee" in the scan). This particular insert shown in the scan was issued in 1945 and was the last of multiple inserts pasted onto these pages of a Soldbuch issued in 1939. I have reproduced this insert

and attached it as a PDF, it is sized to be printed on A4 paper as it

is slightly more than 11 inches long. If you want to print it out but

don't have A4 paper, you can get some larger sized sketch pad paper and

trim it to size, 8.3" x 11.7".

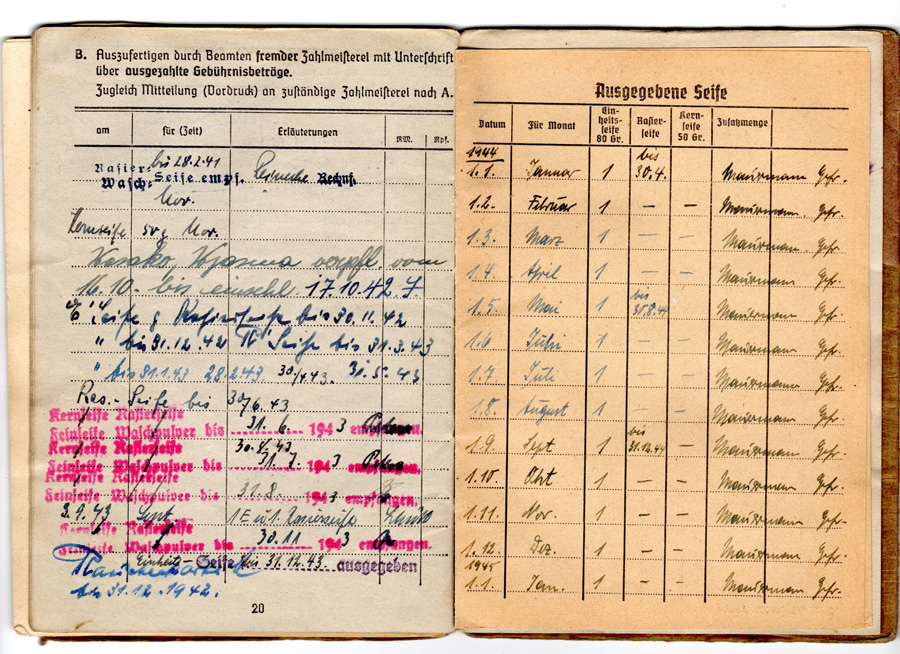

SOAP RATION

Soap was carefully rationed

and controlled in WWII. It fell under the auspices of an authority called

the "Reichsindustriestelle fuer Fettvrsorgung" that controlled soap production and supply. Soldiers in the field may not have been issued soap

and if they were it may not have been recorded. But soldiers in the

rear- in training, garrison troops, convalescents, etc.- were issued soap

and very often these issues were recorded in the Soldbuch, either with a

myriad of stamped or handwritten entries, or as here, with a special

insert page. This particular soldier was serving as a POW camp guard in

Germany during the time indicated on this soap issue insert.

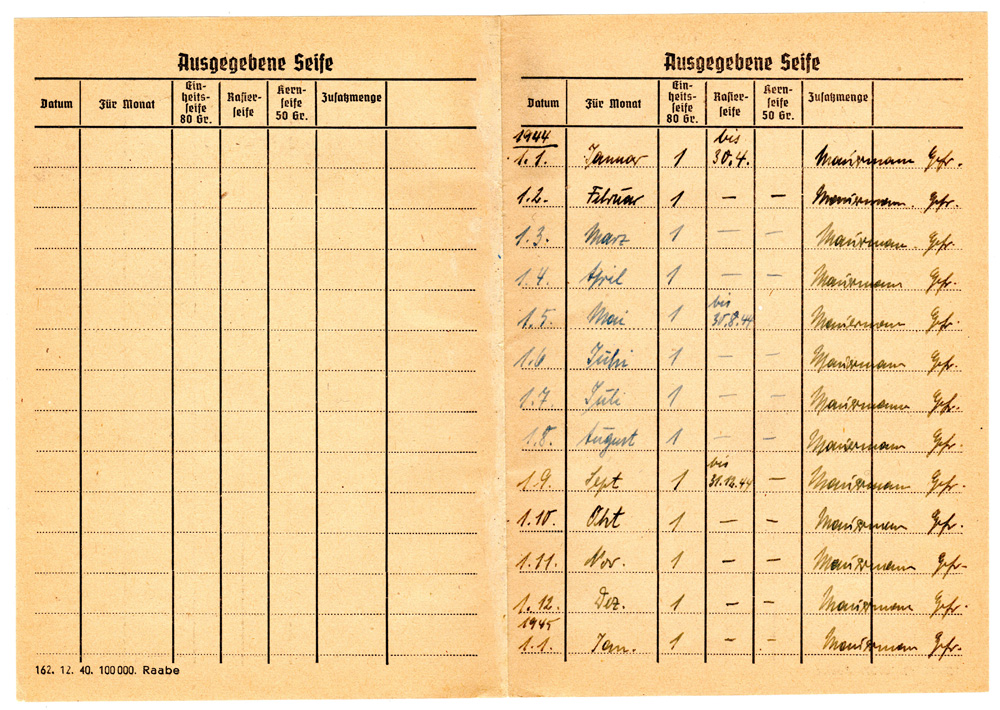

The insert is printed on both sides and folded in the middle to make four pages. It is loose in the book, it may have been glued in at one time. Only one of the four pages has entries. Both sides are exactly the same.

Soap ration insert PDF

To fill this out please refer to the scan of the original. The first column is the date of issue, the next column is to indicate the month for which the samp was issued. The next three columns are for different types of soap: "Einheitsseife" which was an all-purpose soap suitable for whatever purpose, shaving soap, and "Kernseife" which was a type of soap with no natural glycerin that could have been used for washing. The last column, "Zusatzmenge," was for recording additional soap issued. The last two columns are used here for the signature and rank of the soldier receiving the soap, in this case "Mauermann Gefr."

This insert can be used in any Soldbuch for any branch. One exception might be officers as presumably they had to buy their own soap. Virtually every soldier at one time or another was stationed in the rear even if only during recruit training. The original was printed on thin natural-colored paper.

To fill this out please refer to the scan of the original. The first column is the date of issue, the next column is to indicate the month for which the samp was issued. The next three columns are for different types of soap: "Einheitsseife" which was an all-purpose soap suitable for whatever purpose, shaving soap, and "Kernseife" which was a type of soap with no natural glycerin that could have been used for washing. The last column, "Zusatzmenge," was for recording additional soap issued. The last two columns are used here for the signature and rank of the soldier receiving the soap, in this case "Mauermann Gefr."

This insert can be used in any Soldbuch for any branch. One exception might be officers as presumably they had to buy their own soap. Virtually every soldier at one time or another was stationed in the rear even if only during recruit training. The original was printed on thin natural-colored paper.

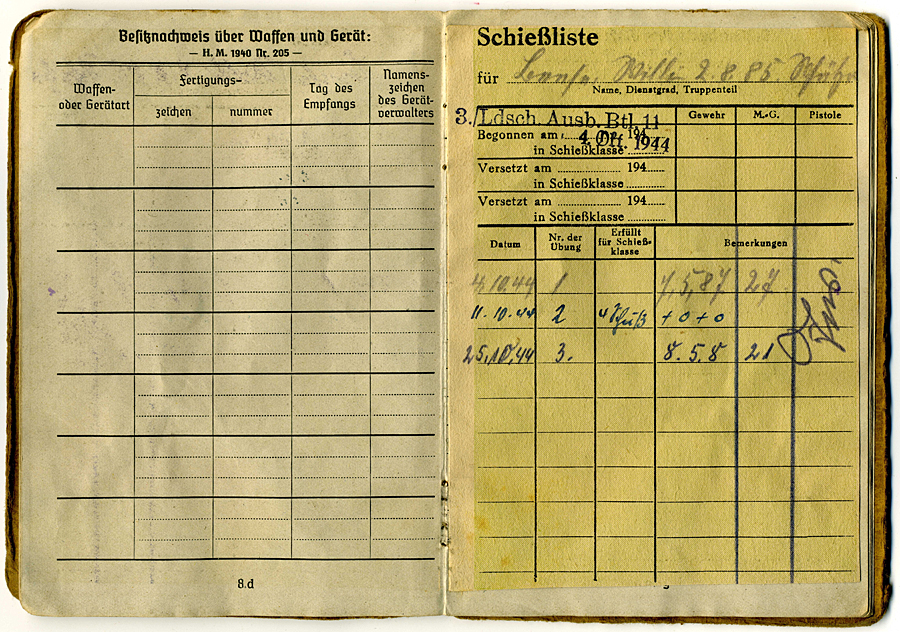

SCHIESSLISTE

Since at least WWI if not earlier, marksmanship training was recorded in a document called the Schiessbuch. During the war, the Schiessbuch was at least partially supplanted by a

number of inserts intended to be pasted in the Soldbuch.

This example was printed on typical wartime paper and had a sort

of green overprint that was probably intended to serve as an

anti-counterfeit measure. The purpose of this insert was to record the

"shooting class" of the soldier for each training session but as you can

see, here, it was just used to record scores. We have reproduced this

document, but without the green overprint.

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Paperwork for a living history impression

Reenactors interested in the finer details of an impression often ask what would constitute an ideal set of paperwork for a

first-person persona. The answer is always that the best

paperwork that a reenactor can carry

is paperwork that he understands and that he can relate to his portrayal.

The

Soldbuch is the crux of personal paperwork and knowing what is written

in there and what everything means is a key step in a first person

impression. The flap in the back of the Soldbuch is a good place to keep

things like reproductions of period photos, most are small and fit in there easily.

Anything that a reenactor can understand and explain and build a story around

will be better to carry than even perfect reproduction paperwork if one

doesn't know what it means or how it relates to the character being

represented.

In the realities of war, there were an endless number of variables regarding what paperwork was carried. There were regulations, of course, but these regulations seem to have been more or less widely disregarded, and much of what was actually carried on a day-to-day basis seems to have depended heavily on such variables as personal preference, unit or type of unit, area of operations, etc. It seems like there were few hard and fast rules as to what was carried and what was not, what was retained and what was discarded. The Wehrpass was not supposed to have been carried by the individual soldier but some soldiers went into captivity carrying these so this must have happened at some times, for some reasons. Having said all that, here are our conclusions based on studies of more-or-less untouched paperwork groupings. Others may have come to different conclusions.

SOLDBUCH: As stated, this was the basic individual ID and is the cornerstone of personal paperwork from a reenactment perspective. Some soldiers were issued Merkblätter which were small leaflets about topics including gas warfare and various ailments, these leaflets were supposed to have been glued into the Soldbuch but the majority of original Soldbücher, including many books issued early on and carried throughout the war on all fronts, do not have these (even when other various documents are still associated with the Soldbuch) and so their issue was either rather limited or the mandate to keep these in the Soldbuch was widely ignored.

OTHER ID DOCUMENTS: Soldiers were issued many different kinds of lesser ID documents which were issued right down to Kompanie level in some cases. This category can include things as simple as small signed and stamped paper scraps attesting that the soldier belonged to a particular unit, as well as various kinds of photo IDs such as the military driver's license or the Dienstausweis, and all kinds of passes and permits.

TRAVEL DOCUMENTS: Soldiers do seem to have retained various kinds of travel documents such as the Dienstreiseausweis or the Wehrmachtfahrschein even when the travel was completed, for whatever reason. There were also documents that permitted soldiers more or less free travel in specific areas for specific purposes, these also seem to have been retained. There were also passes to enter certain cities, some of these were valid only for a specific occasion, others were valid for longer periods.

AWARD DOCUMENTS: Some have stated that award documents were to be kept in the Soldbuch. Based on our studies, we do not believe that award documents were carried in the Soldbuch most of the time. No doubt they were carried in the field for a period immediately after issue, but the official entries in the Soldbuch would seem to make carrying the associated documents redundant.

LETTERS FROM HOME: Regulations stipulated that letters from home were not to be carried in the field to deny the enemy any intelligence contained therein. In reality, soldiers did keep and carry these, sometimes accumulating large numbers of them when circumstances permitted. Feldpost was second only to ammunition in the supply system, and getting mail from home was an important feature of the life of the Landser.

PERSONAL STUFF: By this, we mean really personal. Many soldiers carried small booklets in which they would record addresses or keep records of mail sent and received. Some soldiers kept journals in these small notebooks. They seem to have been very common. Photos of loved ones were also carried by very many soldiers.

EPHEMERA: We find lots of stuff in paperwork groupings that were intended to be discarded but that were kept for whatever reason. A page from a calendar, a little piece of newspaper, a blank form or a receipt for hay or for cabbage, perhaps these were used as bookmarks, perhaps they had some personal significance known only to the soldier, or maybe it was just pocket trash. Some companies would even send advertisements in various forms to soldiers at the front and sometimes the recipients would hold on to these.

CIVILIAN STUFF: Many soldiers seemed to have carried documents related to their civilian lives, even when these documents would seem to have been useless at the front. Insurance cards, post office box receipts, paperwork regarding bank accounts, or similar stuff.

The paperwork that you can carry is limited only by your imagination. We have held many untouched paperwork groupings as carried by German soldiers and have never found one loaded with Reichsmarks and porn as carried by so many reenactors. It is far more common to find a couple of plain-looking pictures, a local provisional ID or travel permit, perhaps a letter from home or a certificate relating to the soldier's civilian life, and a scrap of paper with seemingly random notes, their significance lost to time.

In the realities of war, there were an endless number of variables regarding what paperwork was carried. There were regulations, of course, but these regulations seem to have been more or less widely disregarded, and much of what was actually carried on a day-to-day basis seems to have depended heavily on such variables as personal preference, unit or type of unit, area of operations, etc. It seems like there were few hard and fast rules as to what was carried and what was not, what was retained and what was discarded. The Wehrpass was not supposed to have been carried by the individual soldier but some soldiers went into captivity carrying these so this must have happened at some times, for some reasons. Having said all that, here are our conclusions based on studies of more-or-less untouched paperwork groupings. Others may have come to different conclusions.

SOLDBUCH: As stated, this was the basic individual ID and is the cornerstone of personal paperwork from a reenactment perspective. Some soldiers were issued Merkblätter which were small leaflets about topics including gas warfare and various ailments, these leaflets were supposed to have been glued into the Soldbuch but the majority of original Soldbücher, including many books issued early on and carried throughout the war on all fronts, do not have these (even when other various documents are still associated with the Soldbuch) and so their issue was either rather limited or the mandate to keep these in the Soldbuch was widely ignored.

OTHER ID DOCUMENTS: Soldiers were issued many different kinds of lesser ID documents which were issued right down to Kompanie level in some cases. This category can include things as simple as small signed and stamped paper scraps attesting that the soldier belonged to a particular unit, as well as various kinds of photo IDs such as the military driver's license or the Dienstausweis, and all kinds of passes and permits.

TRAVEL DOCUMENTS: Soldiers do seem to have retained various kinds of travel documents such as the Dienstreiseausweis or the Wehrmachtfahrschein even when the travel was completed, for whatever reason. There were also documents that permitted soldiers more or less free travel in specific areas for specific purposes, these also seem to have been retained. There were also passes to enter certain cities, some of these were valid only for a specific occasion, others were valid for longer periods.

AWARD DOCUMENTS: Some have stated that award documents were to be kept in the Soldbuch. Based on our studies, we do not believe that award documents were carried in the Soldbuch most of the time. No doubt they were carried in the field for a period immediately after issue, but the official entries in the Soldbuch would seem to make carrying the associated documents redundant.

LETTERS FROM HOME: Regulations stipulated that letters from home were not to be carried in the field to deny the enemy any intelligence contained therein. In reality, soldiers did keep and carry these, sometimes accumulating large numbers of them when circumstances permitted. Feldpost was second only to ammunition in the supply system, and getting mail from home was an important feature of the life of the Landser.

PERSONAL STUFF: By this, we mean really personal. Many soldiers carried small booklets in which they would record addresses or keep records of mail sent and received. Some soldiers kept journals in these small notebooks. They seem to have been very common. Photos of loved ones were also carried by very many soldiers.

EPHEMERA: We find lots of stuff in paperwork groupings that were intended to be discarded but that were kept for whatever reason. A page from a calendar, a little piece of newspaper, a blank form or a receipt for hay or for cabbage, perhaps these were used as bookmarks, perhaps they had some personal significance known only to the soldier, or maybe it was just pocket trash. Some companies would even send advertisements in various forms to soldiers at the front and sometimes the recipients would hold on to these.

CIVILIAN STUFF: Many soldiers seemed to have carried documents related to their civilian lives, even when these documents would seem to have been useless at the front. Insurance cards, post office box receipts, paperwork regarding bank accounts, or similar stuff.

The paperwork that you can carry is limited only by your imagination. We have held many untouched paperwork groupings as carried by German soldiers and have never found one loaded with Reichsmarks and porn as carried by so many reenactors. It is far more common to find a couple of plain-looking pictures, a local provisional ID or travel permit, perhaps a letter from home or a certificate relating to the soldier's civilian life, and a scrap of paper with seemingly random notes, their significance lost to time.

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)